Heroes.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012 at 07:41PM

Tuesday, July 31, 2012 at 07:41PM  A tale of sound and fury, signifying nothingI know it rationally, of course. I know that they’re ciphers, blanknesses onto which we project our fantasies, archetypes of a singularity that we wish our lives could possess. Hence Batman, whose single defining purpose is to restore the equilibrium of society, is anodyne enough to satisfy anyone who has ever entertained the fantasy of reacting against perceived injustice – which is to say more or less everyone, from the socialist who dreams of redeeming society from the crushing oppression of totalitarianism to the fascist yearning to liberate society from the dehumanizing yoke of collectivism, or the psychopath obeying imperatives too dark for us to untangle.

A tale of sound and fury, signifying nothingI know it rationally, of course. I know that they’re ciphers, blanknesses onto which we project our fantasies, archetypes of a singularity that we wish our lives could possess. Hence Batman, whose single defining purpose is to restore the equilibrium of society, is anodyne enough to satisfy anyone who has ever entertained the fantasy of reacting against perceived injustice – which is to say more or less everyone, from the socialist who dreams of redeeming society from the crushing oppression of totalitarianism to the fascist yearning to liberate society from the dehumanizing yoke of collectivism, or the psychopath obeying imperatives too dark for us to untangle.

And the same could be said of most if not all the canonical comic book heroes. Partly this is because they’re company owned, so it’s in the interest of the companies to give their property no short-term memory or permanent identity save for a few interchangeable building blocks of narrative. That way, the characters can be perpetually rebooted to anticipate and exploit the latest trends.

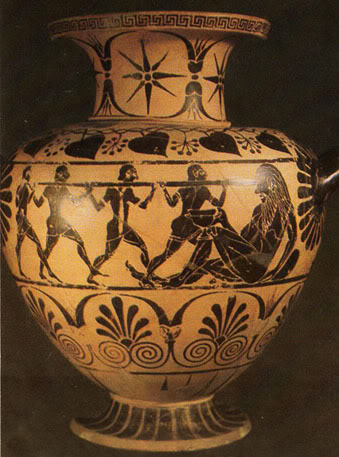

Odysseus blinds the cyclops, Polyphemus.But the ownership angle isn’t really the point. The same revisionism takes place with all heroes, from Odysseus to King Arthur. Our heroes are white spaces on a page with the exception of a few sound bites or anecdotes, some key exploits and noble attributes, and we love them for it – I love them for it. Despite all my rational objections, despite my sincere belief that literature needs to commit itself to excavating the real in order to have any value, I love heroes.

Odysseus blinds the cyclops, Polyphemus.But the ownership angle isn’t really the point. The same revisionism takes place with all heroes, from Odysseus to King Arthur. Our heroes are white spaces on a page with the exception of a few sound bites or anecdotes, some key exploits and noble attributes, and we love them for it – I love them for it. Despite all my rational objections, despite my sincere belief that literature needs to commit itself to excavating the real in order to have any value, I love heroes.

The truth is, I get enough realism from reality, from the maddening feedback loops of my own thoughts and other people’s lives and the general insanity of the world. When I want to relax, I don’t look for pained introspection or avant-garde experiments, even though I recognise the value of such endeavours. No, I want the narrative shapes of epic; I want a hero, a journey, a descent into peril, redemption, and a bunch of really cool one-liners.

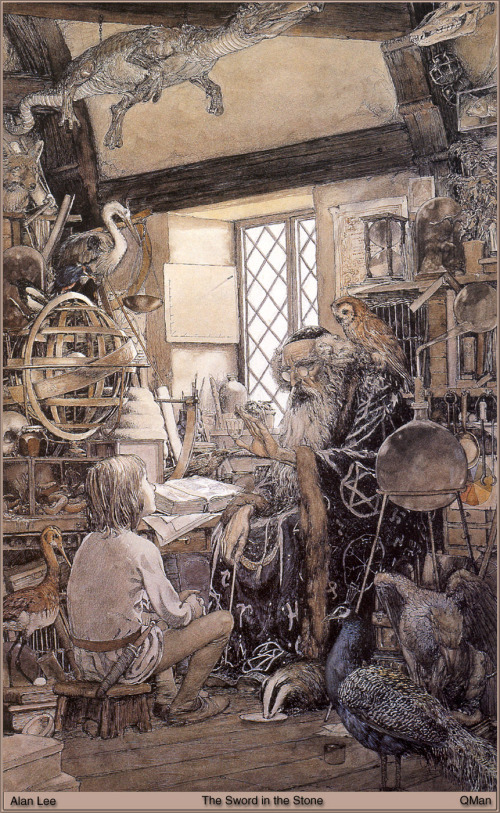

Rex quondam et futurus: King Arthur as a boyI think maybe we need heroes like we need gods, though the compulsion is different. We want our gods to absolve us, to wash us clean. The artistic analogue to this impulse is found not in epic, but in tragedy, where we are exposed to just enough fear and pity to glimpse the fundamental suffering nature of existence, and thereby are renewed. But heroes, and the stories they inhabit, come from a different place. They come from the darkness and the fire, when we told stories to comfort ourselves against shadows and nightly noises. And they don’t suffer, because their stories are endless.

Rex quondam et futurus: King Arthur as a boyI think maybe we need heroes like we need gods, though the compulsion is different. We want our gods to absolve us, to wash us clean. The artistic analogue to this impulse is found not in epic, but in tragedy, where we are exposed to just enough fear and pity to glimpse the fundamental suffering nature of existence, and thereby are renewed. But heroes, and the stories they inhabit, come from a different place. They come from the darkness and the fire, when we told stories to comfort ourselves against shadows and nightly noises. And they don’t suffer, because their stories are endless.

So heroes transcend us, doing all the things we never could. The fact is, we need them, despite knowing that they're not real – indeed, precisely because they're not real. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing, not necessarily an infantile flight from reality. If we accept that humans have always craved these stories, which go by the name of parables in some circles, then we have to accept that the example of a hero leaves a trace residue, a ghostly outline on our minds. It comes back to us when we’re faced with adversity, when we’re trying to think of a good comeback or searching for the courage to act.

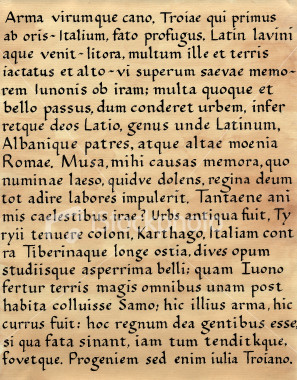

Same old tune: I sing of arms and the man. Virgil's Aeneid.And that can have a positive effect, but it can also have a very negative one. The effect is neither the hero’s fault nor the author’s, because the hero is a movable feast, representing a different truth to each person. We can no more blame a hero for inspiring violence than we can blame a god for religious wars. If it hadn’t been this hero or that god, man would have found another one to justify his behaviour, because that’s what we do, and who we are.

Same old tune: I sing of arms and the man. Virgil's Aeneid.And that can have a positive effect, but it can also have a very negative one. The effect is neither the hero’s fault nor the author’s, because the hero is a movable feast, representing a different truth to each person. We can no more blame a hero for inspiring violence than we can blame a god for religious wars. If it hadn’t been this hero or that god, man would have found another one to justify his behaviour, because that’s what we do, and who we are.

That’s why I think we have a responsibility as an audience to remember that we each need heroes in different yet equally valid ways, and also that, however we need them, heroes are never more than figments of our imagination, quicksilver scraps of another world. Our role as readers is to read our heroes carefully, using that secondary ethical sense which remains active even as we lose ourselves in story, to ask why we love them, why they matter to us.

'They tell you never punch a man with a closed fist. But it is, on occasion, hilarious.' Mal ReynoldsAuthors can help with this process by writing their heroes equally carefully and retaining ownership of them. For example, contrast Mal Reynolds, the hero of Firefly, with DC’s Batman. You would find it very hard to misread Mal Reynolds, because Joss Whedon gave him not only a complete backstory but an entire continuum of flaws and moral imperatives which effectively dictate his responses to each new situation. If you tried to reboot Mal Reynolds, you’d destroy the character’s continuity, and, perhaps more seriously, all the Browncoats would kick your ass.

'They tell you never punch a man with a closed fist. But it is, on occasion, hilarious.' Mal ReynoldsAuthors can help with this process by writing their heroes equally carefully and retaining ownership of them. For example, contrast Mal Reynolds, the hero of Firefly, with DC’s Batman. You would find it very hard to misread Mal Reynolds, because Joss Whedon gave him not only a complete backstory but an entire continuum of flaws and moral imperatives which effectively dictate his responses to each new situation. If you tried to reboot Mal Reynolds, you’d destroy the character’s continuity, and, perhaps more seriously, all the Browncoats would kick your ass.

Now I’m off to watch Rising Damp, because Rigsby's my hero.

Reader Comments